Per-capita dominance, a conveyor belt of WTA champions, and a winning team culture: the Czech blueprint explained.

The Small Nation With the Big Output

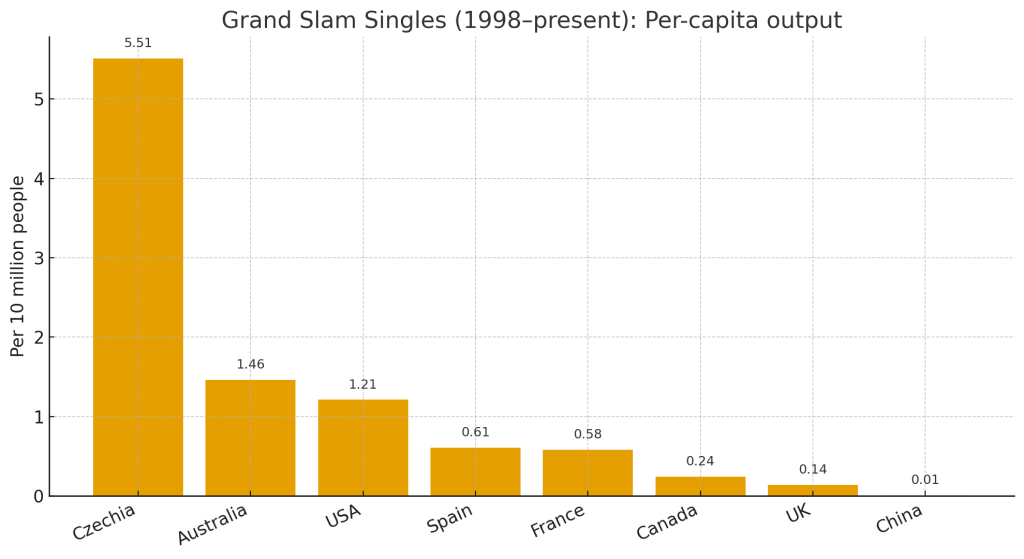

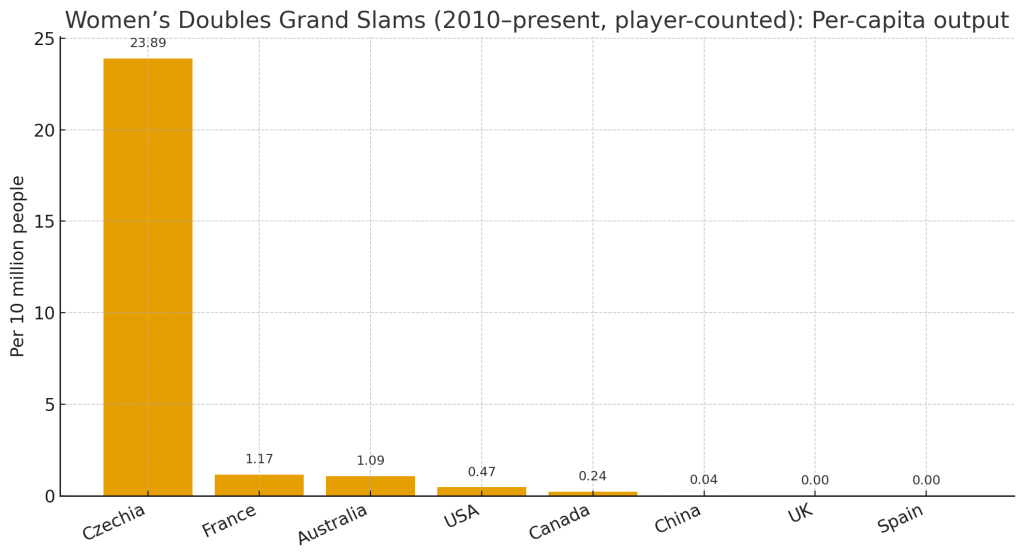

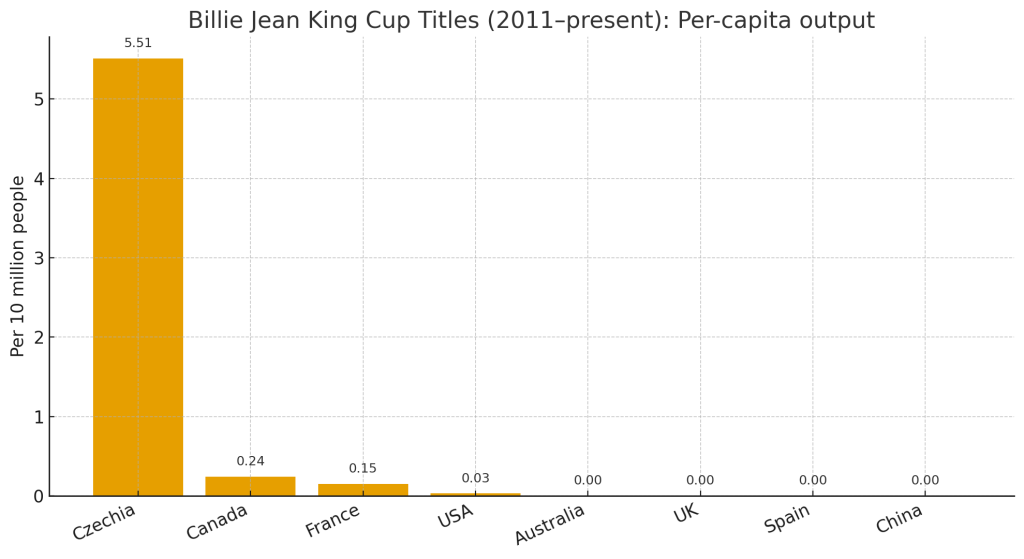

On raw totals, giant federations usually top the charts. Adjust for population and the story flips: Czechia (~11M people) ranks top-three per capita (since 1998) in modern Grand Slam singles, No. 1 per capita in women’s doubles (since 2010), and built a Billie Jean King Cup dynasty (since 2011). That’s not a spike; it’s a playbook.

The core claim, up front

- Singles depth: From Jana Novotna to Petra Kvitova, Barbora Krejcikova and Marketa Vondrousova, Czech champions have arrived in a steady cadence across surfaces.

- Doubles supremacy: A decade-plus of dominance anchored by Krejcikova/Siniakova and reinforced by Safarova, Strycova, Peschke, Hlavackova, Hradecka.

- Team identity: Six BJK Cup titles in eight seasons (2011–2018) underscore national depth and clutch doubles.

“Per person, Czech women produce elite results at a rate big nations don’t match.”

This report lays out how we measure that claim and what the international comparisons show (USA, Australia, UK, France, Canada, China, and Spain). Most importantly— we will explain the five reasons behind Czechia’s sustained success in Part II.

Why Per-Capita Changes the Czech Conversation

Counting trophies rewards scale; counting trophies per person rewards systems. Our methodical approach focuses on the modern era to keep comparisons relevant and auditable:

- Grand Slam women’s singles titles (1998–present) — the post-Novotna window that captures the current system’s footprint.

- Grand Slam women’s doubles titles (2010–present), counted by player — the era of deep, global doubles fields. Counting by player (not pair) attributes each champion to her nation, mirroring how national totals are typically presented.

- Billie Jean King Cup titles (2011–present) — the modern Finals era, which captured the Czech dynasty.

- Population denominators — most recent mid-year estimates.

Why these windows?

- They reflect the current coaching, competition, and travel realities of the sport.

- They reduce distortion from pre-Open Era or fragmented historical structures.

- They allow like-for-like comparisons across nations with different tennis histories.

The per-capita rate used here

We express national outputs as titles per 10 million people

(titles × 10 / population in millions). For team outcomes we do the same, because team triumphs (BJK Cup) are sensitive to depth, not just one superstar. Where appropriate we also discuss unique player counts (e.g., number of distinct Slam-winning women in the period) to avoid over-weighting single-player streaks.

Where Czechia Stands vs USA, Australia, Canada, China, United Kingdom, Spain, and France

This section sets context against seven major markets we included: the USA (scale and legacy), Australia (elite coaching and event infrastructure), Canada (surging pipeline), China (mass participation and growing pro presence), plus the United Kingdom, Spain, and France (each with distinct modern-era signatures). We’ll revisit these comparisons throughout the five‑reasons framework in Part II.

High‑level contrasts

- USA still leads the world on raw singles volume since the late 1990s (Serena & Venus anchoring a deep generation), yet per capita the rate sits below smaller tennis powers.

- Australia punches above weight per capita in both singles and doubles thanks to coaching lineage, centralized resources, and a cohesive calendar; distance limits sparring density but the system remains efficient.

- Canada’s recent surge—anchored by Bianca Andreescu (US Open champion) and Gabriela Dabrowski (US Open doubles champion)—signals a maturing system with upside, capped by a Billie Jean King Cup title (2023).

- China boasts historic Slam breakthroughs (Li Na in singles; Peng Shuai, Zhang Shuai, Wang Xinyu in doubles) and a massive base; per capita, the huge denominator suppresses rates despite meaningful achievements.

- United Kingdom has a standout modern singles peak (Emma Raducanu, US Open 2021). Per capita, output remains modest in the chosen windows; no women’s doubles majors (2010–present) or BJK Cup titles (2011–present) in this frame.

- Spain delivers mid‑tier per‑capita singles in the modern window (Arantxa Sánchez Vicario in 1998; Garbiñe Muguruza in 2016 & 2017). Women’s doubles majors since 2010 and BJK Cup titles since 2011 are absent, keeping overall per‑capita output below Czechia.

- France balances mid‑tier singles per capita (Pierce, Mauresmo, Bartoli) with a strong doubles footprint (notably Mladenovic/Garcia), plus a BJK Cup title (2019)—making it the closest of the three European nations to Czechia on depth‑based metrics.

Czechia’s per-capita edge

- Singles: A top-three per-capita producer since 1998, tracking closely with Switzerland (Martina Hingis effect) and trailing Belgium (Justine Henin & Kim Clijsters), while outpacing much larger nations.

- Doubles: The runaway No.1 per capita in the 2010s and 2020s, driven by a sustained elite cohort.

- Team tennis: Six BJK Cup titles in eight seasons (2011–2018) reflect bench strength and doubles reliability; few nations can field interchangeable pairings with similar upside.

Why Belgium and Switzerland aren’t in the headline tables

We deliberately excluded Belgium because its modern-era per-capita numbers are almost entirely driven by two once-in-a-generation outliers—Justine Henin and Kim Clijsters (11 Grand Slam singles titles combined — Henin 7 + Clijsters 4). In a small-population nation, a pair of all-time greats can spike the per-capita metric so sharply that it stops measuring systemic depth and starts measuring superstar luck. Since our report’s aim is to compare repeatable national systems (breadth of finalists, doubles depth, and team results), we treat Belgium as a special case rather than a benchmark.

We treated Switzerland as a special case (reflecting a single-superstar effect caused by Martina Hingis and her 5 titles, again not systemic depth) and reference it separately rather than include it in the headline per-capita tables.

The Champions: A Continuity of Styles That Solve Matches

Czech champions don’t look identical; they share repeatable patterns: take the ball early, own the return, transition with purpose, and manage tempo under pressure. The results speak across two decades:

- Jana Novotna (Wimbledon 1998): Serve-and-volley fingerprints and a lasting mentorship legacy.

- Petra Kvitova (Wimbledon 2011, 2014): Lefty first-strike grass game refined by elite anticipation and early contact.

- Barbora Krejcikova (Roland Garros 2021; Wimbledon 2024): Pattern mastery—especially from return and mid-court—derived from doubles-honed instincts.

- Marketa Vondrousova (Wimbledon 2023): Disguise, variety, and superior tempo control; a modern problem-solver on quick and medium-pace courts.

- Karolina Pliskova (World No.1, Slam finals): A rankings spine that validated the pipeline’s singles ceiling.

Surrounding those flagship names is a deep cohort—Karolina Muchova the most skillful among them, though her career has been marred by injuries—of Top-50 and Top-100 players, exactly the distribution that wins ties and deciding rubbers.

Case Studies: How the Blueprint Plays Out on Court

Petra Kvitova — Lefty First-Strike Tennis Made Repeatable

Kvitova’s Wimbledon titles (2011, 2014) illustrate the Czech knack for first-strike tennis that doesn’t collapse under pressure. Her lefty serve, early contact, and willingness to take time away from opponents work on grass, of course, but also on medium-fast hard courts. The underlying habits—serve location discipline, return court positioning, and early backhand timing—are trainable. That’s the Czech point: the spectacular emerges from repeatable foundations.

Training implications drawn from Kvitova

- Lefty/righty serve patterns are scripted and drilled (e.g., deuce wide → backhand open; ad T → forehand jam).

- Cross-court backhand timing is rehearsed early in development to neutralize pace.

- Short-ball conversion is not optional work; whole sessions are devoted to neutral-to-offense transitions.

Barbora Krejcikova — Pattern Mastery from Doubles

Krejcikova’s singles major at Roland Garros (2021) and Wimbledon (2024) came from a toolbox sharpened in doubles: returns that start rallies on her terms, mid-court touch, and positional awareness that shrinks opponents’ options. As a singles player she isn’t the tour’s heaviest hitter; as a pattern manager she’s elite.

Training implications drawn from Krejcikova

- Sessions bias the return game (e.g., return targets by score, depth+direction combos).

- Doubles patterns (poach reads, middle ball calls) convert into singles habits (step-ins, early cuts, knife-volleys).

- The ability to reshape tempo (off-pace to draw short replies, then step in) is treated as a teachable skill.

Marketa Vondrousova — Disguise and Tempo Management

Vondrousova’s Wimbledon title (2023) showcased a different Czech superpower: deception and tempo control. Her lefty angles, drop-shots that punish overextended stances, and elastic defense that flips points reveal a training culture comfortable with variety. The moral isn’t “be tricky”; it’s “own the speed of the exchange.”

Training implications drawn from Vondrousova

- Build two speeds into practice—fast to take time, slow to draw errors—and toggle on command.

- Treat the drop shot and short slice as positioning weapons, not just point-enders.

- Make disguise an intention (same take-back, different delivery) rather than a hope.

Karolina Pliskova — The Rankings Spine

Pliskova’s rise to World No.1 in 2017 validated the singles ceiling of the Czech system. Her serve economy, measured risk from baseline, and trust in patterns made results feel inevitable. Put differently: the system creates players who know their game—and that predictability is an asset at the top.

Training implications drawn from Pliskova

- Serve as the foundation of weekly planning (locations, patterns, +1 decisions by score).

- Shot selection rules articulated and rehearsed; players learn when not to do too much.

- Confidence is framed as repeatability, not mood.

Per-Capita Comparisons

We summarize the key comparisons without turning the report into a wall of tables.

Singles (1998–present)

- Czechia sits near outlier nations Belgium and Switzerland (not in our headline tables due to single-superstar effects) and ahead of much larger nations. The point is consistency: champions and finalists arriving across different eras and surfaces.

- USA leads on raw totals, but when divided by population the rate trails the Czech cluster.

- Australia also fares well per capita given a smaller national base and a focused high-performance pathway.

- Canada shows a modern surge; per capita it has meaningful signals but a smaller sample.

- China has landmark wins; per capita the rate is naturally lower because of its vast population.

- United Kingdom registers a singular modern spike (Emma Raducanu, US Open 2021); across the full window the per‑capita rate is modest.

- Spain lands in the mid‑tier per‑capita band (Arantxa Sánchez Vicario in 1998; Garbiñe Muguruza in 2016 & 2017) with no recent team or doubles lift to amplify the signal.

- France also profiles mid‑tier per capita in singles (Mary Pierce 2000; Amélie Mauresmo 2006; Marion Bartoli 2013), supplying breadth but not enough recent volume to challenge Czechia’s rate.

Women’s doubles (2010–present, titles counted by player)

- Czechia dominates the rate metric, powered by Krejcikova/Siniakova and a supporting cast of major‑winning Czechs.

- USA’s doubles tradition remains strong but not close to Czechia per capita in this window.

- Australia posts a healthy per‑capita doubles output, closely tied to training emphasis and pair continuity.

- Canada and China register on the board with champions, confirming that breadth of national programs is rising globally.

- France is a clear doubles bright spot among the added nations—Kristina Mladenovic and Caroline Garcia lift France to a meaningful per‑capita rate in this window.

- United Kingdom and Spain show minimal output in women’s doubles majors since 2010 under the player‑count method.

Billie Jean King Cup (2011–present)

- Czechia’s six titles in eight years represent a depth‑driven dominance; few nations can swap pieces without losing cohesion.

- USA and Canada have added titles in the modern Finals era; Australia has contended deep; China remains a sleeping giant in team competition with plenty of future upside as its pro cohort expands.

- France added a 2019 title, the strongest team‑tennis signal among the three newly added nations, while the United Kingdom and Spain have none in this window.

What the Numbers Don’t Tell You (But Czech Coaches Will)

Per-capita rates are powerful, yet they’re proxies. Coaches inside the Czech system will add more texture:

- Daily density matters: It’s not just how many courts exist, but how close good practice partners are. Czechia’s geographic compactness helps players get lots of quality reps without heavy travel.

- Shared language reduces friction: Players step between teams, academies, and captains without relearning terms. That saves time and nerves.

- Doubles pressure as a classroom: Break-point returns, “I-formation” reads, and mixed responsibilities under time pressure build nerves of steel—useful in Slam second weeks.

Practical Takeaways for Federations and Academies

Other nations often wonder how to replicate Czechia’s outcomes. Here are pieces that might travel well:

- Make doubles core in the development pathway (U14–U18), not optional—design weekly templates where doubles-specific skills bleed into singles (e.g., return+2 volley drills, poach-read footwork into singles transition patterns).

- Codify pattern language (serve locations, return positions, neutral-to-offense triggers) and keep that vocabulary consistent across age groups and coaches.

- Maximize match density locally (club leagues, money tournaments, national series) to normalize pressure reps without constant long-haul travel.

- Build a coaching conveyor that rewards knowledge sharing—shadowing, film-room access, debrief templates—so innovations don’t stay siloed.

- Emphasize first-four shots in weekly planning; it matches how points are actually decided under pressure.

The Road Ahead: Why the Model Still Works

Even as global parity rises, Czechia’s blueprint remains fit for purpose. The next wave—Linda Noskova, Tereza Valentova, Sara Bejlek, Linda Fruhvirtova, Dominika Šálková and others—comes preloaded with the same development DNA: early contact, return clarity, and doubles instincts. As captains evolve and veterans rotate out, the blueprint endures because it’s embedded in clubs, not just in national camps.

Risks and counters

- Injury cycles can thin depth temporarily; the conveyor mitigates this by constantly graduating ready players.

- Calendar shifts (balls, court speeds) might reward different patterns briefly; Czech training emphasizes adaptable decisions over a single style.

- Global imitation will close gaps; Czechia’s answer is speed of learning—the conveyor’s real value.

(Note: Part II is soon to be published)